Formless Forms

Anne Holtrop wanted to be an artist, and has become one through architectural means. Born in 1977, graduated in 2005, and with an office in Amsterdam since 2009, his first works, from the Trail House to the Temporary Museum, were artistic commissions, and both their fluid curves and their topographic dimension are present at the iconic 2011 Fort Vechten Museum. At the labyrinth of caves of the Batara Pavilion of 2013 he uses a gestural materiality that informs his later work, and the 2014 competition for the Bahrain Pavilion at Expo Milano led him to meet his future wife, the Palestinian architect Noura Al Sayeh Holtrop, based in the small island country of the Gulf where she is Head of Architectural Affairs, and his move there to start a new life. From his studio in Muharraq, Holtrop has built projects in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia or the Emirates, all of which have in common an artistic intention through formless forms, and which also benefit from their architectural scale.

Sculptor Richard Serra complained about artists being second-class citizens when measured against architects in commissions, because these get buildings while artists only obtain a work on a square, and his rivalry with Gehry at the Guggenheim to achieve the visibility of size is well-known. The key figures of land art, Robert Smithson or Walter De Maria – both admired by Holtrop – tackled this issue with territory and landscape, and other artists like Gordon Matta-Clark or Ai Weiwei have done the same intervening on buildings or assuming the same role as the architect, taken to an extreme by the latter when designing with Herzog & de Meuron the monumental Bird’s Nest. Holtrop in fact performs as an artist in his Gulf projects, making true what Jacques Herzog has often defended: that artists can do architecture just as architects art. Qaysariyah Suq or Green Corner Building, like the projects in Riyadh for a congress center and a museum complex, can only be read as artworks.

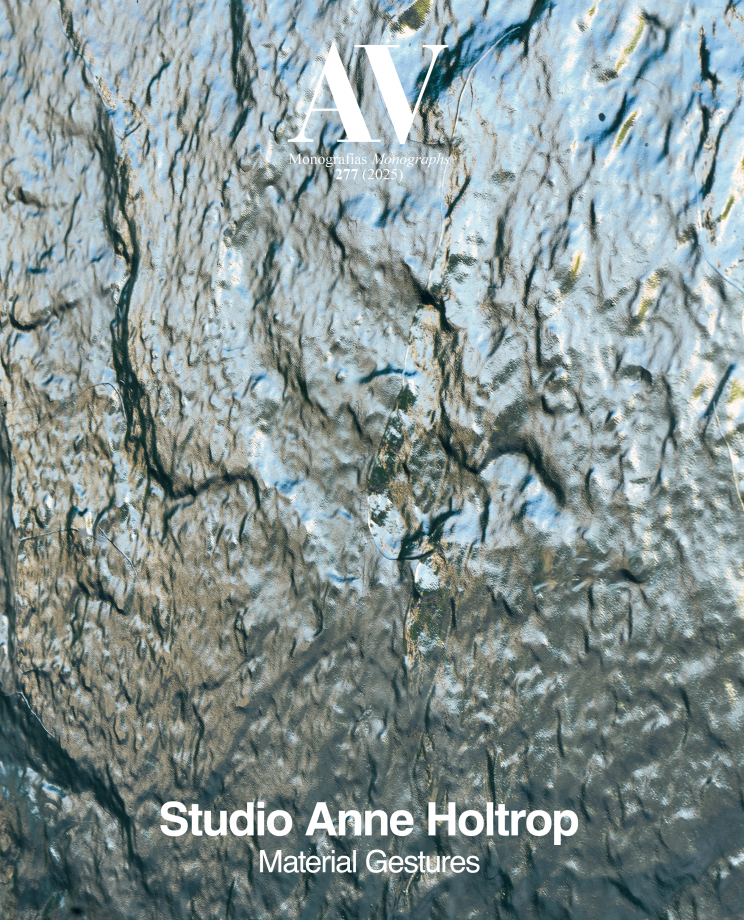

If the projects by the Dutch architect can be seen as formless forms, the oxymoron abridges a set of material features – from rugged textures to mineral objects – and expressive gestures – from excavated perforations to fluid casts – that abrupt dislocations and haphazard cuts transfer from the friendly field of the opera aperta to the sordid and sublime atmosphere of romanticism. Surrealist rather than dada, and Masson rather than Arp, this material art – which to the Spanish eye evokes Tàpies and Millares, Fisac or García-Abril – inevitably recalls the exhibition that Yves-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss opened at the Pompidou three decades ago, and where ‘The formless’ was given four attributes: horizontality, pulse, base materialism, and entropy. I do not know if the path that leads from Batara to Bataille is a legitimate analytical tool, but I am sure that Anne Holtrop, in his journey from Amsterdam to Muharraq, has taken a huge step to materialize the ambitions of a childhood in which he dreamt of becoming an artist.